etcher

|

Notes of the author The underlying theme of this cycle of etchings is the

multifaceted and sometimes complex relationship between symbols and saints and

takes inspiration from the iconographic tradition between the Renaissance and

Baroque, in which the saints and their stories are an integral part. The saints are mostly portrayed as candid and innocent young

girls and as bearded adults and it was and is not easy for everyone to

recognize their identity today. Often the only way to identify them are their

symbols, or what are called, more properly, the iconographic attributes that

always accompany them, that are the objects they hold in their hands or that

are at their side, the animals placed nearby or the heads of clothing. The

attribute par excellence for all martyrs is the palm leaf, a symbol of

sacrifice but also of triumph over Evil and a sign of their Redemption. These attributes derive their origin from the hagiographies

of the saints and from the Acts and Passions of the martyrs in which their

sacrifice and all the brutal tortures that preceded it are

recounted, often romanticizing them with bloodthirsty tones. All this tradition

will be collected and reworked in 1265 by Jacopo da Varagine, Dominican friar

and bishop of Genoa, in the book called Legenda aurea

which was widespread

in the Middle Ages so much so that it was considered one of the first

bestsellers in history. These writings constitute the source and

inspiration of the entire European iconographic tradition which

elaborates, in the wave of widespread devotion, an identifying code for the representation of saints, which will have value from the Middle Ages to modernity. This code

has the aim of allowing the recognition of sacred characters even to

the least cultured observers, because as Gregory the Great wrote

"painting is for the illiterate as writing is for those who know how to

read". Thus, for example, the attractive and elusive Fillide

Melandroni, the prostitute known throughout Rome for her extraordinary beauty,

becomes in Caravaggio Saint Catherine of Alexandria , due to the symbol of her

martyrdom, that toothed wheel which was the instrument of her torture , by a

miracle, it will break saving her. Following this prodigious event, the saint

will be beheaded with the sword, another of her attributes, which in fact is

found in her hands while at her feet is the inevitable palm leaf. Thus in the etching dedicated to Saint

Catherine, the wheel is not found at her side (as tradition dictates) but in

the foreground at the saint's feet, intimately connected to her symbol, which

constitutes the founding element of the figure itself. By replicating itself

upwards, the wheel changes into another structure, as if to symbiotically protect

the palm tree that grows near it. The image ends with a book, because the

martyrs are the witnesses, the true interpreters of the Word (see also Saint

Simon), while the multifaceted face enclosed in the large volume refers to the

triple nature of saint, martyr and woman. Even in the etching dedicated to Saint Lorenz his main

attribute, the gridiron on which he was burned alive, is converted into a complex

reticular structure which acts as a base and support for a sort of ecumenical

embrace with the classical lines of an empty amphitheatre, often a place of

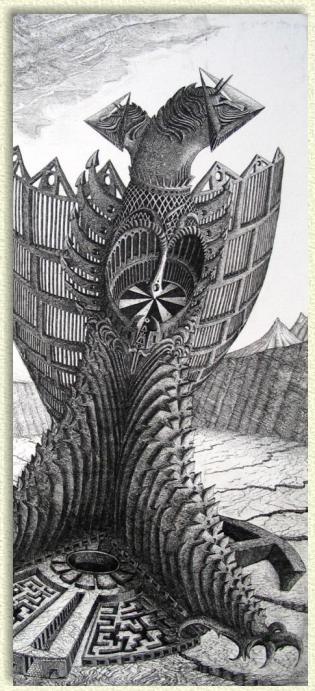

torture. In some etchings, the symbol seems to take on hypertrophic

forms such as to almost completely occupy the perspective space: this is the

case of Saint Margaret. The martyr, on the night before her execution, was

visited in the prison cell by the devil in the form of a dragon who swallowed

her. Margaret, armed only with the cross, tears open the monster's belly and

survives the lethal confrontation. From this ancient initiation rite, a passage

towards a higher level of consciousness (see Jason and Jonah but also

Pinocchio) Margaret will emerge as a martyr as a saint and will become part of

a small number of saints, the 14 holy helpers, that is, those who they are

invoked in the moment of greatest danger. She will be the saint destined to

protect women giving birth. In the engraving the martyr is not captured, as

tradition dictates (Raphael and Giulio Romano), in the moment of triumph over

Evil but in the midst of the fight with a monster which, however, has nothing

horrifying but seems to be a prop ( the little key), destined to play a role already

pre-assigned and functional to the dramatic representation. Even in the etching of Santa Barbara her symbol dominates

the scene. The saint seems to be in the middle of a bloody fight with the tower

in which she was segregated by her father. Armed with the same sword with which

she will be executed as a Christian, opens a gap between the two sides who are

about to give in to her powerful push. But her head is itself a tower to remind

us that, even if Barbara succeeds in her aim, she will have to deal with an

internal "enemy", just as solid and resistant as her prison. Even the symbol of Saint Andrew, martyred on the cross that

bears his name (an X-shaped cross), is placed in the center and in front of the

same figure, contrary to the tradition in which he is always behind the saint

or at his side ( Rubens and the statue of Duquesnoy in St. Peter's). In the

engraving the saint is forced to perforate his symbol with tunnels to proclaim

his existence. The symbol, placed at his feet but also in the sky, would like

to suggest how its meaning has changed over time: from the religious

and martylological sphere of the Christian tradition it has been transmuted into

an emblem of the unknown and the enigmatic nature of existence (De Chirico, Metaphysical composition). Even the railway carriages are a citation of the

modern in art (Magritte, Time transfixed) but also an observation that that

symbol also belongs prosaically to the nomenclature of the railway world. Even in Saint Erasmus, bishop of Antioch and holy helper,

his symbol, the winch, occupies the central space. Mounted on a imposing structure collects, by rolling them,

the intestines of the martyr condemned to evisceration (the removal of the

internal organs), a torture often represented in tradition with inevitable

truculent and brutal tones (Sebastiano Ricci , Giacinto Brandi or Nicolas

Poussin). The sentence seems to allude to the persecutors desire to tear from

the body that faith whose revolutionary message they did not understand. The

long poles are an explicit reference to the Leggenda of the

True Cross of Pier della Francesca, when the Jew Judas is pulled from the well into which he had been

thrown, to convince him to reveal the place where the cross of Christ was

buried. The martyr's intestines, however, pierce his body and seem to come from

a much deeper cavity, beneath the marble sarcophagus on which he was abandoned,

while his soul, with large spirals, already circles far away in the sky towards

that much-desired Paradise. Saint Helena is the main character of the aforementioned Leggenda of the True Cross and is always represented with the cross. Elderly

mother of the Emperor Constantine, in 327-328, she undertook a long and

dangerous journey to the Holy Land to the places of the Passion of Jesus,

inaugurating what would become one of the most famous pilgrimages in history.

Like an archaeologist ante litteram, she wants to find the cross on which

Christ died after three centuries. He will find it again and bring a fragment

of it to Rome, where the basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme will be built to

house it. Another case of hypertrophy of the symbol observed in Santa

Margherita is found in the engraving dedicated to San Florian. The soldier of

the Roman army was thrown into the river with a millstone around his neck in

Upper Austria, for having defended the Christians. The millstone has become a

mammoth pair of oil mill wheels in the grip of an unstoppable inertial motion,

which will bring the saint to his tragic end. The scene described for the

setting (the wooden log bridge and the river) is an explicit debt to Albrecht

Altdorfer's Martyr of Saint Florian, even if in this there is no trace of the saint's

resigned acceptance in his youthful nudity. There is a fundamental ambiguity in

the scene. A legionnaire is dragged by the invincible motion of the powerful

millstones to which he is bound but, at the same time, it is not known whether he

desperately tries to govern the motion in some way or instead supports it,

aware of his destiny, towards the tragic fatality that waits for him. The

ambiguity perhaps derives from the fact that in the sacrifice of the saints,

for us moderns, it is difficult to distinguish between an Imitatio Christi

taken to the extreme consequences and the tragic impulse towards immolation and

self-annihilation. This theme also recurs in Saint Sebastian. Officer of the

Roman army and protector of Christians, naked like Christ, he is martyred by

arrows, which he will survive by miracle. For this reason he is invoked as a

holy thaumaturge in case of illnesses or epidemics, often together with

Saint Rocco, another holy healer. Tradition (for all Mantegna, but also Reni) represents

him with his young ivory body and perfect shapes, serene and triumphant over a

martyrdom that should be deadly. In the etching that bears his name, hanging

like Christ from the column, there is what remains of a cataphracted black

body, tragically prostrate by agony and now almost lifeless. Above the column

to which it is tied, there are tentacled spirals, a symbolic motif that intends

to represent the power of the Church, whose strength is based on the sacrifice

of the saints, whose testimony (martyrs in Greek means "witnesses")

is fundamental for the transmission of his religious message to the entire

world, which takes place through a sinuous and disturbing antenna. In the other version the saint, riddled with arrows on a

battlefield, is literally petrified by pain. Maybe a fatal collapse awaits him

or maybe he will be able to at least raise his head towards that tiny symbol of

redemption on the mountain in the distance. However, there is no trace of Saint Clement, bishop of Rome

and fourth Pope in the history of the Church. Only its symbol, the anchor,

stands out in the desolation of a desert. His presence is only evoked by the

vestments with the insignia of the head of the Church and by the ponderous

missal, from which the end of a crozier protrudes. The large iron anchor

commemorates his sacrifice, when it was tied around his neck before being

thrown into the sea from a ship. Legend has it that in the place of martyrdom,

the sea retreated for a few miles every year, so much so as to reveal the shrine

with his remains, an incessant destination for devout pilgrims. There is also no evidence of Saint Apollonia,

but it is her

symbol, the tooth, that tells us about her. The saint was the victim of

an

anti-Christian riot in Alexandria in Egypt in the 3rd century. Her

Passio

recounts her torment preceded by torture during which all her teeth

were pulled

out with pincers. The molar, femininely refined, seems besieged by a

decomposed mob of tongs and torture claws. The candor of the symbol and

its

isolation are the manifest signs of its superiority and at the same

time of its

holy intangibility. Sometimes the symbol happens to multiply. This is the case

of Saint Agatha, patroness saint of Catania. The story of her sacrifice says that

among the many tortures her breasts were torn or cut off. This is why in the

iconographic tradition, from Piero della Francesca to Zurbaran, the saint is

represented with the palm of martyrdom in one hand while in the other she holds

a plate on which her severed breasts are found, like a small still life. In

this engraving the symbols have quadrupled as well as the arms, making a

comparison with the Indian goddess Kalž and the Greek Demeter of Ephesus almost

inevitable, in a syncretic representation of a Christian virgin martyr who is,

at the same time, a mysterious pagan divinity and potentially dangerous, like

the volcano in the background. The multiplication of the symbol is so

irrepressible that visible signs of it can also be observed in the domes of the

towers of the city walls and in the high clouds in the sky. Even in Saint Simon we witness the same phenomenon of the

multiplication of the symbol. Simon, apostle and saint, is a fisherman from

Galilee, hence the symbol of the boat. Having become an evangelical

"fisherman of men", (the book is also one of his symbols) he

suffers martyrdom in distant Armenia. His body is cut to pieces with a saw,

probably like that of the lumberjacks of the past. The triplication of the

symbol aims to underline the fury of the martyrdom of a venerable saint

transformed into a tree, whose roots sink precisely into that boat on the shore

of that remote lake, which he left forever following the Word of Jesus. The image of Saint Peter instead arises from the

juxtaposition of the keys, his main symbol, and the dome of the most important

church in Christianity. The keys inserted in the keyholes seem to allude to the

fact that they do not open the kingdom of heaven but some mysterious secrets

kept in the sacred institution, while that of the saint seems to be able to

unlock the unfathomable depths of theological thought represented by the books. Saint Denis

appears to have no symbol but in reality it

is his own head, which he holds in his hands, that is his

characteristic

emblem. The saint was bishop of Paris (Saint Denis) and martyred in

Montmartre

(Mount of Martyr). He is a cephalophoric saint, that is, a saint whose

hagiographies say that, after his decapitation, he collected his own

severed

head, holding it with his hands. The posture of the image of the saint,

gothically dressecd under a black cloak, with one foot propped up on a

low stone

parapet, is a direct reference to San Florian by Francesco del Cossa,

which

was placed in the upper left compartment of the Griffoni Polyptych. The saint

holds his head with bishop's miter and gas mask on his right knee. Faced with

devastating Roman repressions, the first Christians were non-violent fighters of

immense courage and had to face the deadly and poisonous persecutions of an

enemy who could not understand the profound reasons for their faith. The mask

of Saint Denis is in turn the symbol of this patient and firm Christian

resistance, which will allow the new religion to triumph over the persecutors. The traditional representation of Saint Lucy is no different

from that of Saint Agatha (often portrayed together). In her martyrdom her eyes

were torn out which she shows as her symbol on a plate or cup. For the

engraving that bears his name, the iconographic point of reference is still

Francesco del Cossa, who portrayed Saint Lucy in the right compartment of the

aforementioned polyptych. In this painting the saint, with a highly original

invention, holds in her left hand a flower stem from which not two buds but her

own eyes emerge. That stem with the saint's eyes can also be found in the

engraving, in a small transparent vase near the figure. In the scene

represented, the posture of the saint and the ladder leaning against the

cornice are quotes from Durer's Melancholia. The martyr, deprived of sight and

with her face hidden by the bandages that cover the mutilation, seems to want

to look through another eye placed on her knees (with the eye of Horus in the

center) to see that invisible that only the soul can see. Saint Cecily, martyr and patroness of music, is almost

always represented with a small portable organ in her hands or at her side

(Raphael and Orazio Gentileschi), even if the reason for this association still

remains uncertain. The engraving is an explicit homage to Arcimboldo's art,

founded on the combination of objects from a single semantic area,

metaphorically connected to the subject represented. In this way the image of

the saint is assembled solely with an accumulation of musical instruments,

while her symbol, the organ pipes, are transformed into a sort of sonorous

vegetal backdrop to the scene. Like other saints (see Santa Agnese and Sant'Antonio) Saint

Rocco also has an animal as its symbol, a dog. French pilgrim (hence the

attributes of the cloak, the staff, the hat and the flask) is headed to Rome,

where he treats and heals the sick of the plague epidemic that raged in Italy

in the second half of the fourteenth century. During the return journey he

falls ill with the terrible disease and isolates himself in a cave so as not to

infect other people. What saved him from illness and starvation was a dog who

provided him with bread every day. The most invoked thaumaturge saint,

often represented with Saint Sebastian, is portrayed in tradition, offering the

viewer his bare thigh to show the bubo that has appeared near his groin. In the

engraving, the traveler-saint is blocked from moving by the contracted disease

and his wounds are exposed like the cavities of an old diseased trunk. The

saving dog, with the insignia of Saint James, comes from the sky and has just

landed to help him, bringing the bread that will heal him definitively. Saint Agnes also has an animal as her symbol, the lamb,

because, like the small animal which in turn symbolizes Christ's sacrifice, she

is slaughtered with a sword blow to the throat. Roman saint of noble origins,

before the final execution she was condemned to the stake but the flames, by a

miracle, split under her body and her hair grew to cover her nakedness. The

lamb in his arms has its front legs tied, a reference to Zurbaran's Agnus Dei,

but it also has the shape of a space probe that from the depths of the universe

has landed on the "wrong" planet and in the arms of a woman with whom

to share an identical destiny. San Blaise, Armenian bishop, was martyred in 316 three years

after the Edict of Milan, which granted freedom of worship to Christians. His

torturers tore his body using iron combs, which were used to card wool. A

further condemnation seems to be that of carrying these enormous and heavy

instruments of torture on his old shoulders, in the last journey he travels

leaning on a stick that ends with two intertwined candles (another attribute of

his), the light of which seems to indulge his uncertain and tired step. Saint Christopher is like Saint Blaise a helper saint and

patron saint of travellers. He was a giant ferryman who one day helped a child

cross to the other side of the river. The giant lifted him onto his shoulders

and began the journey; but the further he went into the river, the more the

boy's weight increased, so much so that with much difficulty he managed to

reach the bank. There the child revealed his identity: he was Jesus and his

burden that the giant (Christopher in Greek means "Christ-bearer")

had supported was that of the entire world saved by the blood of Christ. This

extraordinary meeting will transform Christopher into an evangelizer and then

into a martyr. St. Anthony

was a hermit from Egypt who lived between the third and fourth

centuries and the founder of Christian monasticism. Like other

anchorites of the time, he abandoned the city and took refuge in the

desert of the Thebaid, bearing witness to his faith with a solitary and

radical asceticism. It was in the desert that his disciples found

him unconscious and covered in sores and burns. They were the signs of

the struggle with the devil who had come to tempt him with his

monstrous assaults. Anthony overcomes the brutal temptations of

the Evil and the fires of hell by showing the courage and firmness of

the first Christian martyrs. And for this reason he will become a much

loved and recognizable saint because of the monk's robe, the

T-shaped stick and the pig, from whose fat those liniments were

obtained, which were the only remedy against that devastating "fire"

that bears his name. In the engraving, St Bartholomew suffers martyrdom as 'that fig tree' under which Christ first saw him, perhaps near the shores of the lake. On the ground, the remains of a violent flaying, on a tree shaken by an axe blow that split it in two, testifying to how disruptive, in the Saint's life, was the power of the Saviour's Call and his Word and how they definitively changed his life, marking his destiny towards martyrdom and holiness. St. Jerome is one of the most representative and complex figures in the history of Christianity. Father and Doctor of the Church, St Jerome was a theologian, biblical scholar and Latin translator of the biblical text (the Vulgate); he was secretary to Pope Damasus I and destined to succeed him; he was a monk and anchorite in the Syrian desert of Chalkidiki. In 385 A.D. he left Rome for good and retired to a convent in Jerusalem, dedicating himself to study and meditation. There are two main iconographies of the saint: that of the solitary anchorite in prayer, in the desert or in the grotto of Bethlehem, with a crucifix, skull and stone with which he beats his chest in sign of penitence (CosmŤ Tura, Antonello da Messina, Pinturicchio, Leonardo, Durer, Lotto); and that of the wise theologian, portrayed in his study-library attending to the translation of the Bible (Van Eyck, Colantonio, engraving by Durer, Antonello da Messina). In the latter case he is shown in cardinal's robes and wearing a galero (hat), sometimes thrown to the ground as a sign of his renunciation of honours. In the latter context, a lion often appears. Legend has it that, at the monastery in Palestine where he was staying, a lion burst in with a paw wounded by thorns, causing panic in the small community. Instead of fleeing in fear like his brethren, the saint approached the animal and cured it; the lion tamed and as if to show his gratitude remained faithful to him until his death. Among the manuscripts in his study, the saint holds the animal's paw in his hand, resting on the Gospel, and both are pierced by the nail of Jesus' sacrifice, a symbol of that Christian compassion, of that mercy, of that piety that encompasses and accumulates all human beings but extends far beyond, to embrace all living beings on Earth, with whom men are destined to share the same ephemeral destiny. St. Piertus Martyr,

belonged to the Order of the Friars Preachers, founded by Dominic of

GuzmŠn, in 1213, to fight, in collaboration with the Inquisition,

heretical movements and first and foremost Catharism, which had spread

from southern France. To eradicate this heresy, the Church

engaged in a twenty-year crusade (1209-1229) with devastating

persecutory ferocity. A crusade fought among Christians in Christian

territory and considered by many historians to be the first example of

genocide. In the meantime, the heresy had also spread in Italy,

especially in Lombardy where it was now widely rooted. In 1251, Pope

Innocent IV appointed him inquisitor for the cities of Milan and Como,

with a mandate to repress all forms of heresy. On 6 April 1252, while

Pietro was on his way from Como to Milan, near a wood in Barlassina he

was attacked by an assassin, armed by heretics, who violently hit him

on the head with a billhook, killing him. The assassin repented

his act, took refuge in a convent, became a Dominican friar and was

granted the title of blessed. Eleven months after his death, Peter was

proclaimed a saint and martyr and his cult, supported by the Order,

quickly spread throughout Italy. Iconography usually depicts him

in Dominican habit with a dagger in his chest and with a billhook, his

main attribute, deeply embedded crosswise in his head, a macabre detail

that cannot escape the observer and that makes him immediately

recognisable (Guercino , Bellini, Cima da Conegliano). In the

engraving, the two crossed billhooks, marked by the Cathar cross,

plunge their blades not into the saint's head but into the dome of St.

Peter's, the symbol of the Catholic and Roman Church, because that was

the real target for the heretics, that was the real enemy to fight in

that attack that was yet another massacre in a bloody crusade that

lasted three centuries and erased the Cathars from history forever. In traditional iconography Stephen the Protomartyr, the first martyr of Christianity, wears dalmatic, the liturgical robe of deacons, but his main attribute is the stoning stones, which he sometimes wears on his head or shoulders (Giotto and Crivelli). In the engraving, we find him lifeless in the rigidity of death, as if he were of the same substance as the instruments of his torture, those stones that would remind us of all the martyrs who, after him, would follow him in the ultimate sacrifice and who would constitute the stones on which the Church would be built. His hand still clasps one of them, as if he himself had also participated in his own martyrdom and testifies, at the same time, to that forgiveness that he asked God for from his killers, shortly before he expired. Saint Eustace had a vision. During a hunting trip he chased a deer that broke away from the herd. When they were alone, the animal spoke to him. It had a glowing cross between its antlers and it was Christ who asked him to follow him in his faith. Eustace chose Christianity and was baptised with his whole family by the bishop. After various tragic ordeals he rejoined his family and resumed service as an officer in the Roman army. Under Emperor Hadrian he was arrested as a Christian and sentenced to death together with his wife and children, after miraculously escaping the lions of the Colosseum. On 12 October 120 AD Eustace and his family died inside a deadly execution instrument called the bull of Phalaris. It was made of bronze and shaped like the animal and large enough to hold a few people. A great fire was set underneath and the condemned men locked up died of fatal burns in excruciating pain. In tradition, the symbol of St Eustace is the stag's head bearing a cross between the antlers as seen, for example, on the banner holding Durer's St Eustace in Paumgartner's altarpiece. In the engraving, the flags between the huge antlers are a direct reference to that work. The head has been transformed into a kind of hypogeum temple with large horns on either side as a reminder of the saint's martyrdom. Replacing the cross is the monogram enclosed not in the traditional crown, symbol of victory, but in the uroboro, symbol of eternity. St Longinus was the Roman centurion present at Christ's death on the cross. To shorten his agony, instead of breaking the bones of his legs as prescribed by the law, Longinus, as an act of mercy and to ascertain his death, preferred to strike Jesus' side with the tip of his spear. Blood flowed from the wound and miraculously cured him of an eye ailment. The saint embraced the Christian faith and, according to one legend, became an evangeliser in Cappadocia and suffered martyrdom by being beheaded for this. Traditional attributes of the saint are the spear, which over the centuries became a legendary relic, and the helmet, as can be seen, among many representations, in the colossal statue dedicated to him by Bernini in the Vatican. In the engraving, the symbol was multiplied out of all proportion and was transformed from an attibute into the instrument of an atrocious martyrdom for the saint, or what remains of him, a kind of empty mortal shell, abandoned next to the cross that marked his destiny forever. St Hippolytus, an austere and cultured priest and theologian, lived in the time of the Severan dynasty, between the end of the 2nd and the first decades of the 3rd century AD, in an era of religious tolerance that allowed the Church to reorganise itself but also to split internally in baleful splits. Hippolytus had gone so far as to accuse the pontiff Saint Zephyrinus himself and his deacon Callistus of heresy. When the latter was elected pope in 217, Hippolytus had himself elected to the same office by his acolytes, effectively becoming the first anti-pope in Church history. The schism persisted until the pontificate of Saint Pontian, when with the end of the Severans, in 235 A.D., the new emperor Maximinus put an end to the policy of religious freedom and had the two popes arrested and deported to Sardinia, condemning them to forced labour in the mines. Here Pontian and Hippolytus were reconciled and both were martyred and became saints. According to a Passio, the body of St Hippolytus was tied to horses and dragged through the dust like that of Hector tied by Achilles to his chariot, under the walls of Troy. According to other sources, the martyr's body was quartered by tying his hands and feet to horses drawn in different directions, as depicted in the triptych dedicated to the saint by the Flemish painter Dieric Bouts. In the engraving, the scene of the martyrdom, which takes place in a kind of arena, is depicted at the moment when the lifeless body of St. Hippolytus, reduced to a meagre mannequin with vague human features, is about to be finally disarticulated by the fury of the forces that are tearing him apart. Only the small laurel wreath recalls, in the agony of his now unrecognisable limbs, his sacrifice for the faith and his eternal sanctity.

|

|

|